WCP: The Unanswered Question about the Future of US Labor Unions

Posted in News Working-Class Perspectives | Tagged Wade Rathke

On Labor Day, Americans celebrate workers, including the accomplishments of labor unions. What might the future bring for American unions? Will new leadership at the AFL-CIO bring new energy to organizing? In Working-Class Perspectives this week, Wade Rathke weighs in on these questions.

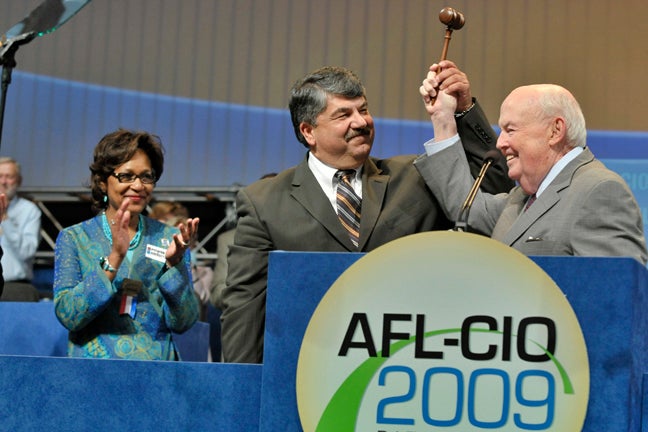

Within six months the two men who have led the AFL-CIO for more than twenty-five years, John J. Sweeney and Richard Trumka, have passed away. In reflecting on Trumka’s sudden passing and the likely transition of leadership within the dominant US labor federation, Steven Greenhouse, the acknowledged dean of labor reporters on the beat for the New York Times, summarized his observations with this telling note: a Gallup poll indicates that “nearly 50 percent of nonunion workers told M.I.T. researchers that they would join a union if given the opportunity.” Trumka’s challenge was how to get those “who want a union into a union, despite intense corporate opposition.” The question, Greenhouse asked, is whether a new AFL-CIO president would have more success.

That question, almost more eloquent than Trumka’s obituary, lands with a thud. A hammer blow to the head. In tallying the pluses and minuses of Brother Trumka’s career, Greenhouse had already recorded Trumka’s failure to meet this challenge in the negative column. Sadly, we also know the likely answer to the question for the AFL-CIO’s new leader, Liz Shuler: a resounding no. The head of the federation, especially as currently constituted, will never have “success” in building mass organization to revive the labor movement.

First, AFL-CIO leaders don’t see this as their job. Second, even if they did, and, arguably, for a while John Sweeney tried, the federation is not structured to allow direct organizing and certainly not mass recruitment at the scale now desperately needed.

The fact that the AFL-CIO is a federation, a voluntary association of autonomous labor organizations, is both its strength and its weakness. As a voice for labor, putting all of the various pieces, large and small, rough and smooth, under one roof, allows the federation to speak, advocate, and lobby for both organized and unorganized workers. But this structure doesn’t make it easy for a federation to act, especially where some level of consensus and veto power can disrupt even the most trivial decisions. Organizing demands action and always, invariably, requires defense from the leaders at the top and movement, sacrifice, and courage from the rank and file below.

Shuler’s answer to the organizing question is already clear. She offers the standard rationale and talking points. The 10% spent on organizing isn’t trivial. It also doesn’t represent all of the other off-budget support that the federation provides through research, communication, legal support, and, undoubtedly, mainly, the bully pulpit. Furthermore, the AFL-CIO is on record supporting things like the SEIU’s Fight for Fifteen campaign, which cost tens of millions but did not gain a single member. Add to that the fact that her service in the labor movement comes from the IBEW construction side, largely as a seasoned lobbyist, first in Oregon and then DC. No matter how she might evolve, politics is more the cell count in her blood more than organizing. At 51 years old in the tradition of the AFL-CIO, Shuler could direct the organization for another 25 years, if it survived in any recognizable form.

The missing link that dashes any hope that the AFL-CIO will ever lead a revitalization of organizing and put the “movement” back behind the word “labor” is the recognition that contemporary institutional unions in the US are political organizations more than worker organizations. Though democracy in unions is often only skin deep, leaders still are elected and advance based on their skill at navigating the rungs up the political ladder in their organizations. The unorganized do not vote. Only members vote. Members might like to hear that their union is talking about organizing, but unless it materially advances their own situation or contract, most care primarily about the union in their workplace and how their dues are used to advance their interests. Feelings of class solidarity, dreams of working-class power, organizing the unorganized are all fine and good, but leaders by and large are elected for delivering to existing members not potential members.

Nowhere is this truer than in the building and construction trades where for the most part the old school is the only school. Their role within the AFL-CIO is outsized compared to their membership numbers. And they exercise their influence conservatively. If the AFL-CIO executive council was weighted by per capita, we would be having a different discussion. If the Building and Construction Trades Council and its member unions, except possibly the Teamsters and maybe the Laborers, were carved out of the AFL-CIO, it would be a totally different organization, and the answer to the question of organizing the 60 million – along with many others – would be very different. In the existing labor federation, political skills are paramount. Shuler’s background fits what many affiliated unions see as the real purpose of the federation, the arena where politics and legislative lobbying fit like fingers in a glove.

The challenge of moving the 60 million who would like a union – or at least some kind of workers’ organization on the job – to become members also faces the limitations of the National Labor Relations Act. AFL-CIO leaders have never been able to make the Act work to help build a mass organization, as evidenced most recently by the defeat at the Amazon plant in Bessemer, Alabama. We haven’t organized a single private sector mass employer in fifty years. Not Walmart. Not Amazon. Not McDonalds. Not any of the giant tech monsters. In fact, no enterprise that has more than 10 or 20,000 workers in this entire period has become union.

Yet, no matter the leader and no matter the union, we continue the love-hate relationship with the NLRB without doing the hard work or spending the resources to develop a new organizing model that can organize the 60 million to have power on the job and elsewhere. It won’t be the AFL-CIO that answers these questions, and as union density decreases and with it the resources to develop a new model and organize the unorganized, it may be impossible for any union to solve this riddle on its own. Certainly, SEIU has tried — and thus far failed. The AFL-CIO and many of its member unions will survive at some level, but organizing the unorganized is our moonshot. We’d like to get there, but it would take more than we have to make the journey. Maybe we’re waiting for our Bezos or Musk to pay the bills and show us the way? Who knows? In the meantime, the question is answered, sadly, and the death watch continues, even if many refuse to change, and we can’t all hear the rattle.

Wade Rathke, ACORN International