WCP: Dirty Jobs, Essential Workers, and the Infrastructure Bills

Posted in News Working-Class Perspectives | Tagged James Catano

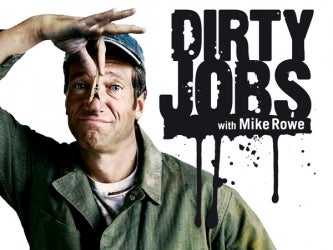

Current negotiations over the second infrastructure bill may remind a lot of people of Mike Rowe’s oddly popular series Dirty Jobs. Which makes sense. Watching a man stumble around inside a sewage tank as he gags loudly and directs us toward closeups of turds, rancid grease balls, and darkly bubbling sewage can clarify a lot about infrastructure negotiations.

That isn’t a sarcastic comparison. Rowe actually talks directly about infrastructure in Dirty Jobs, and the kinds of jobs he highlights and what he ignores can help explain recent disagreements over what qualifies as ‘real’ infrastructure. For some, infrastructure means material structures: bridges that allow traffic and goods to flow smoothly. For others, infrastructure includes workers who support society at its base, such as meatpackers who provide goods moving over those bridges, or day-care workers who help parents find time to actually have a job.

Clearly, how we define infrastructure and essential workers reflects our attitudes toward jobs that society needs in order to function but all too often considers dirty work: labor tinged with social and/moral taint. Everett Hughes’s “Good People and Dirty Work” and Eyal Press’s recent Dirty Work both discuss such morally tainted work: debt collectors, prison and concentration camp personnel, sex workers.

But when we think of infrastructure, we’re more likely to think about the kind of jobs that Ruth Simpson, Jason Hughes, and Natasha Slutskaya consider in Gender, Class, and Occupation: Working Class Men Doing Dirty Work. These jobs are physically dirty: refuse collection and street cleaning, butchery, coal mining. This sort of dirty work is the central core of Rowe’s Dirty Jobs.

Running for nearly 10 seasons, Dirty Jobs offers viewers both specific examples of dirty work and a broader understanding of infrastructure. Both the show’s content and Rowe as its narrator gained wide-spread popularity, particularly among blue-collar workers eager to see their labor displayed up close and personal.

Yet that popularity contains an inherent social paradox. While we know that dirty jobs have to be done, we usually try not to notice work that offends us, especially jobs that are morally tainted. But Dirty Jobs argues that we should see this work, especially that involving physical labor. It actually revels in displaying dirty jobs, visualizing such work fully and in detail, even as the series is properly “cleaned” to exclude morally compromised topics.

In short, Dirty Jobs features jobs high in “ick” factor but relatively low in ethical complexities. As in gory horror films, scenes are intended to shock and disturb by laying bare the permeability and deeply fluid nature of the human body and its related activities.

Equally important is Rowe’s attention to boyish, even grade-school humor material: things that are inside of or come out of bodies in various ways, some natural some decidedly not. Fecal matter — human crap, worm poop, bat guano; bodily corruption—roadkill, animal slaughter; and jobs connected to sex—artificial insemination; all loom large in early episodes of Dirty Jobs, setting its tone from the start. As Rowe himself notes, episodes are regularly “repulsive, repellant, raunchy, and rank.”

Such forms of physical dirt and bodily leakage are usually taboo, so they are either hidden or publicly visualized only in ritualized form. The standard pattern of episodes of Dirty Jobs makes it both a formalized practice and a delightful form of rule-breaking, further enhancing its boyish good humor.

To no small degree, that humor is key to defusing disgust. Rowe stands in for the audience, with his amateur performances and ongoing commentary working on many levels: pulling back the curtain, allowing both direct participation and physical distance, visually enacting horror, disgust, and enough humor to smooth the dangerous edges on all those reactions.

Rowe is also careful to insert respect, genuine or appalled, for the people who perform these jobs. That stance not only contributes to his popularity, it also provides insight into how we think about infrastructure. These jobs are usually hidden from public view because they are unpleasant, but Dirty Jobs argues they should be recognized and valued. Rowe’s visualization and valorization of dirty work forces us to take a useful and necessary look at our attitudes about dirty work and essential workers.

Unfortunately, Dirty Jobs also unintentionally reveals some deeper biases hidden in dirty work. For many, the dirty jobs that count as infrastructure require physical strength, have elements of danger, are ‘tough’ and demand a corresponding toughness and mental control. But what separates a job cleaning sewage tanks from a job wiping the asses that produce that sewage? They’re certainly united through the same by-product. Is there a messier or more important social job than child-rearing? Nursing? Caring for the elderly? Not really. But we don’t see much of that in the series.

These dirty jobs are probably considered uncinematic: too ‘quiet,’ too lacking in dramatic action and large-scale physical effort. When Rowe cleans things, they usually aren’t hotel rooms. Instead, he cleans elevator shafts, waste holding tanks, bridge girders. These dirty jobs are entertaining because they visually enact the physicality associated with masculinity, as opposed to forms of labor seen as feminine or even ‘women’s work.’

Dirty Jobs thus offers a double reveal. It shows and admirably lauds dirty work too often kept “out of sight and out of mind,” as Rowe puts it in one episode. But it also unintentionally reminds us that some forms of dirty work – especially those done primarily by women and immigrants – remain hidden and deeply undervalued. Most of the workers featured on the series are white and male.

Not surprisingly, these doubly hidden biases are echoed very closely in the infrastructure bills. The initial infrastructure plan focused on fields dominated by men—building and highway construction, waste treatment, railways, the power grid. As was true for Dirty Jobs, this bill succeeded by reinforcing traditional, masculine notions of hard, dirty work.

Jobs dominated by women—childcare, health, early education—were put off for the second bill because they didn’t fit outdated notions of infrastructure. Is there a way to change those outdated notions? Can we imagine a Dirty Jobs II that shifts cultural thinking about essential work? One thing we do know: such a series will have to show that the labor of caring for others is not only hard, dirty work, it’s important work, work as essential as new bridges or smooth roads. That really shouldn’t be too hard a job to tackle.

James V. Catano is producer/director of Enduring Legacy: Louisiana’s Croatian Americans and author of Ragged Dicks: Masculinity, Steel, and the Rhetoric of the Self-Made Man. He is Professor Emeritus of English and Screen Arts at Louisiana State University.