SCOTT: What My Grandfather Taught Me About Economic Justice

Posted in Student Leaders | Tagged Alabama, Amanda Scott, International Paper, Labor History, Strike, Student Leaders, United Paperworkers International Union

Amanda L. Scott is an Alabama native, D.C. transplant, civil rights paralegal in the Georgetown University Class of 2019.

I was born and raised in a working-class family in Chickasaw, Alabama, a small shipbuilding company town just outside of the port hub of Mobile.

My father dropped out of school before the ninth grade and immediately went to work as a sandblaster at a naval shipyard. My mother worked several odd jobs throughout her life, notably as a textile factory worker, a waitress at the Waffle House, and a cashier at Wal-Mart.

Then there was my grandfather. He worked 41 years at the International Paper Company and was a life long member of the United Paperworkers International Union.

One of my fondest childhood memories was staying over at my grandparents’ house on the weekend. Or, as I lovingly called them, Memaw and Papaw. I remember wearing Papaw’s over sized ‘Proud to be Union’ t-shirt as we stayed up late together eating popcorn and watching reruns of Matlock.

Played by TV legend Andy Griffin, Matlock was a sharp criminal defense attorney determined to uncover the truth and prove his client’s innocence. My grandfather was like Matlock. Not just because they both had white hair and an eccentric personality, but because of their shared commitment to justice.

Many nights Papaw had to work the graveyard shift at the paper mill— 12:00 A.M. until 12:00 P.M. — and he would leave for work just as Memaw and I were headed to bed. A proud family man, he did what he had to do in order to support my grandma, my mom, and my aunt.

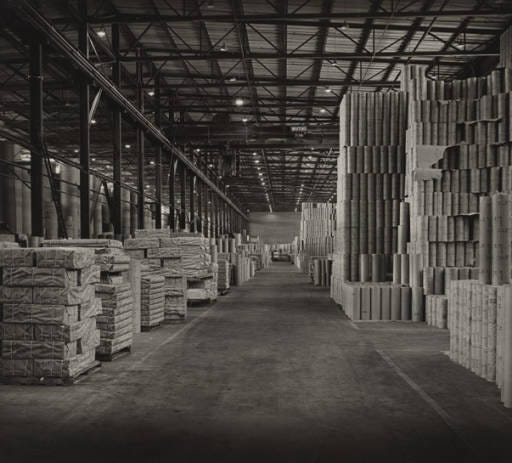

Interior of the warehouse of the International Paper Company mill in Mobile, Alabama. Photo courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History.

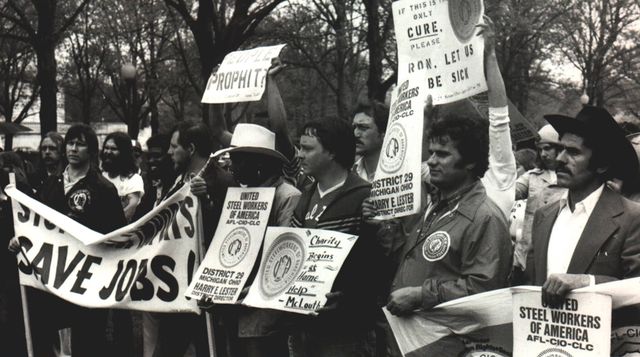

In 1987, the International Paper Company proposed several cutbacks in employee benefits, including eliminating Christmas as a paid holiday and Sunday premium pay. These changes came at a time when the company was making record high profits.

My grandfather saw the injustice of an international, multi-billion dollar company cutting back the benefits he and his fellow workers had worked for. So he joined 1,200 workers and went on strike against International Paper, which sparked similar actions across the country.

Mobile had been dubbed “the union capital of the South.” 90 percent of the workforce at International Paper was unionized. The union tried to enter negotiations with the company on behalf of the workers to protect the benefits that they had been guaranteed.

But instead of reaching a compromise, what the company did was lock out the 1,200 workers on strike from entering the building. In solidarity with their fellow union paper workers in the South, Northern workers went on strike at mills in Maine and Pennsylvania.

When I was researching this strike, I was expecting to read a happy ending where my grandfather and his fellow workers had stood up against IP and won. But what I learned was that, like the issues of our own time, the pursuit of justice is a continuous struggle that is never easily won.

During the dispute, International Paper advertised job openings to replace the workers on strike. Scabs, who may have just been other working-class people with their own families to support, were eager to cross the picket line and accept the jobs.

Once the workers had been replaced, the union lost any real bargaining power to negotiate with the company. Some of the older workers — like my grandfather — were able to get their jobs back but without the benefits they had fought for.

Despite the workers’ defeat, my grandfather still put me in his Proud to be Union t-shirt and taught me the importance of standing up for what’s right, even when you’re on the losing side, and to keep on fighting until you win.

The International Paper Company shut down in 2000 and my grandfather passed away in 2012.