WCP: We Need a Working-Class Ranking System

Posted in Visiting Scholars | Tagged Allison L Hurst, Higher education, John Russo, Sherry Linkon, WCP, Working-Class Perspectives, Working-Class Students

Lists that rank U.S. colleges are everywhere these days. You can find images of the “most beautiful” or “safest” campuses on Facebook. Every major news magazine seems to have its own rankings system. All of this started with US News & World Report’s “Best Colleges” ranking, first published in 1983 and used by generations of college-going students and their parents as the definitive guide. Even as we are bombarded with these rankings, however, we also hear stories of their flaws. And although colleges bemoan the distorting effects of the rankings, they willingly submit information to the major ones to be sure they’re included. And students keep looking at them.

As a sociologist, I’ve always found these lists troubling. There are literally dozens of reasons why. You can’t really quantify the value of education, and the lists often ignore significant differences among types of institutions. Rankings reinforce a competitive urge — among both students and institutions — that is unhealthy, to say the least. They too often reward schools with prestige. They also encourage colleges to spend money in ways that will improve their rankings but don’t always align with the core educational mission. They are sticky, too – most institutions never move very far up (or down) the lists.

As a working-class academic, however, what rankles me the most is the distorting effectsthese rankings have on college admissions policies. Level of ‘selectivity’ is a key metric in U.S. News’s ranking, and this encourages schools to become more exclusive. A school can lose its position if it is viewed as being too easy to get into. This is why Princeton was crowing recently about its lowest acceptance rate ever (5.5%). Similarly, some ranking systems consider average time to complete a degree, a metric that favors colleges with students who don’t have to work, take care of their kids, or worry about debt. This emphasis on efficiency may encourage schools not to accept lower-income students, who often take longer to graduate because of these concerns. For similar reasons, residential colleges will always outrank commuter colleges.

Now this wouldn’t be quite so bad if policymakers, funders, and state governments were not beginning to use these very same rankings and the metrics they’ve developed to reward and punish colleges. We should all worry about the impact this will have on schools that serve non-traditional students, low-income students, first-generation students, and students from the working class. The current craze for rankings may directly impact only the handful of students attending selective colleges, but it is having severe downstream effects on all colleges, especially those struggling to fund higher education for the broader public. This is why I argue that how we rank colleges is a working-class issue. The time for ignoring them and hoping they will go away has long passed.

We need to start, first, by collectively asking what we want our colleges to do. Do we want to reward colleges for reproducing privilege (like the “Best Colleges” list), or do we want to reward colleges that transform students’ lives? And, if the latter, how do we measure such a thing?

A few groups have suggested alternative rankings systems that attempt to correct for some of these distortions. The Washington Monthly ranks colleges based on their contribution to the public good, one measure of which is how many low-income students attend and graduate. Others are focusing more on outcomes, such as Raj Chetty, whose approach has received a lot of well-deserved attention. Using state-level tax records, Chetty and his colleagues compared the median incomes of graduates with their parents. This let them rank colleges by how well they promoted social mobility (for example, moving into the top 10% of earners from the bottom 60%). And when you look at these rankings, you see that the “best colleges” don’t always do a good job with this — a healthy corrective to U.S. News, which includes absolutely zero information on these issues.

While these alternatives move us in a better direction, I think we should demand a working-class friendly alternative ranking system. We can begin by asking what information working-class people who are interested in higher education need. We can also pursue a more complex scorecard system, like the one proposed by the Obama administration.

I’ve been working on a model for this. The first thing is to look at outcomes relative to where students start. A college that admits students with an average 900 SAT score and graduates them to decent jobs is more successful than a school that admits students with an average 1300 SAT score and does the same. In my model I created a “lack of privilege” index that considers the percentage of low-income students and students from underrepresented minority groups along with selectivity and test scores. This data factored against the economic returns for each college yields a raw “score” of the impact of each college. When I run the numbers, Harvard ends up with a score of 21, while UT-El Paso, one of the highest scorers, earns a score of a 109.

Those are raw scores. I also think it’s important to include items of particular relevance to working-class people considering college. For example, what percentage of a college’s graduates are unable to repay student loan debt? And how many students end up dropping out? When I add these factors in, I end up with an overall score. UT-El Paso still beats out Harvard. By a lot.

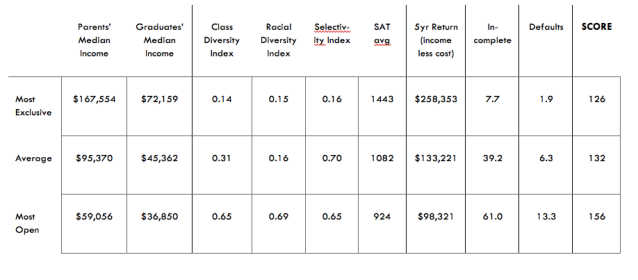

At this point I make an acknowledgment to reality in that students who are seriously considering Harvard are probably going to be considering other equally selective colleges and not the most open access colleges. So I decided to compare colleges, and score them, only against those in their own “bands of selectivity.” You can take a look at what three of these bands look like in included table.

It shouldn’t surprise us that our most exclusive colleges have wealthier students than the most open colleges, but that is perhaps also why their graduates earn higher incomes. In terms of scores, though, the higher scores are found as one moves down the chart to the most open colleges, and this is because I constructed the system to measure transformational impact rather than prestige.

In my system, MIT (not Harvard) ranks very high among the most exclusive colleges; Rutgers and Texas A&M score high among average colleges; and UT-EL Paso earns its top ranking among the most open colleges. Within each category, graduates of these four colleges do much better than would be predicted by their test scores and social backgrounds. I won’t name the colleges here that earn failing grades, but their graduates often struggle to earn enough money to repay the cost of college.

This approach emphasizes where students start instead of just looking at how much money they earn after graduation. Given how important higher education is to the possibility of social mobility in the US today, why haven’t we developed a way to identify which colleges actually contribute to the social mobility of their students? Perhaps we have not wanted to look too closely, preferring the rosy forecasts of the “average” college graduate. But we owe our students, especially those who are the first in their families stepping on this path, some real guidance.

Read the post in its entirety and other WCP posts on our website.