WCP: Low Cotton: A Class on Class

Posted in Visiting Scholars | Tagged Alabama, Helen Diana Eidson, Higher education, John Russo, Labor Studies, Sharecroppers, Sherry Linkon, University of Alabama, WCP, Working-Class Perspectives, Working-Class Studies

Students will only understand class politics and working-class culture if it is part of their college curriculum. In this week’s Working-Class Perspective, Helen Diana Eidson describes how she creatively engaged her students at the University of Alabama on the issue of class through the history of Alabama cotton sharecroppers.

In fall 2015, I taught undergraduate and graduate versions of a course called Rhetorical Theory and Practice at Auburn University in Alabama. AU was founded as a men’s college in 1856, but it is now a research university with strong programs in agriculture and engineering. Most of our students come from Alabama, Georgia, and Florida, but few are well acquainted with the Southern system of peonage implemented after Reconstruction, a system that relied on a non-food commodity: King Cotton. While landowners lived in “high cotton,” white and black sharecroppers and tenant farmers dug themselves a little deeper with every hard-won crop, mired in a system designed to control them.

They were digging themselves into a hole I have come to call “low cotton.” These farmers were subjected to the disciplinary gaze of landowners and “polite society,” thereby objectified and alienated from their work. They sold their bodies and minds for a pittance, eking out a bare subsistence despite sacrificing their families’ security, health, and well-being. How was this system designed, and why was it perpetuated? How were the oppressed able to discover and enact their agency? These are some of the questions my students and I explored. We considered difficult truths, connected grand ideas to humble stories, and reflected on our own positions and perspectives within today’s global, neoliberal economic reality. To help students wrestle with complex and challenging questions like these, I rely on five principles: proximity, primary, past, provocation, and praxis. While these reflect my training in rhetoric, they can apply in many fields and contexts, not only in classrooms but also in union halls and community centers.

They all rest on praxis, Brazilian educator Paulo Freire’s understanding of the interplay between “action” (practice) and “reflection” (theory). My students read critical theories that enable them to think dialectically about contradictions such as subject-object, mind-body, master-slave, and male-female; to understand texts as cultural productions shaped by hegemony and ideology; and to see how working-class subjects can gain what Freire calls critical literacy, the class consciousness (Lukacs) of organic intellectuals (Gramsci) that enables people to claim agency and act upon material conditions. Students not only study action and reflection, but they also engage in action and reflection: they act by crafting arguments for public audiences, and they reflect in informal class writings about what they learned and how well their writing strategies worked.

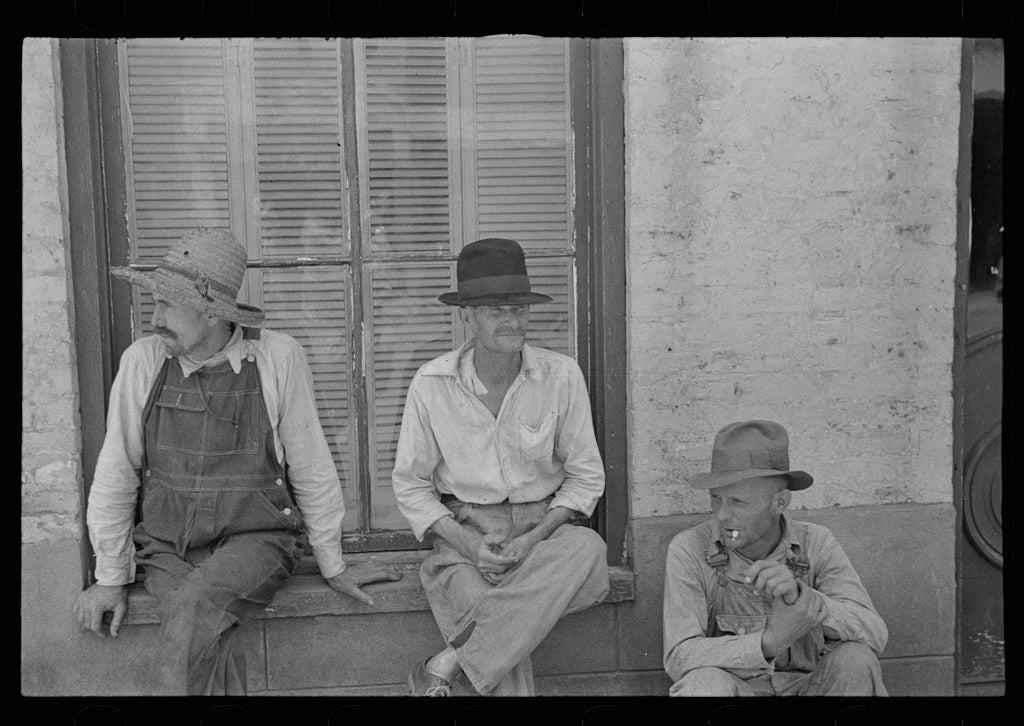

Proximity means focusing on local communities and contexts. When we study global economic systems—and we must—we sometimes have difficulty not only in perceiving the scope and implications of systems but also in applying the global to our immediate lived conditions. Proximity also addresses the need to “think globally, act locally.” As a land grant university, Auburn’s mission is to serve Alabamians, and most of our students call Alabama “sweet home.” That’s why I assign readings that portray communities to which students can relate and issues in which they can engage. In Rhetorical Theory and Practice, we read oral histories such as All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw by Theodore Rosengarten (1974); social documentaries such as Let Us Now Praise Famous Men by James Agee and Walker Evans (1941); and historiographies such as Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Depression by Robyn D.G. Kelley (1990). Agee and Evans especially stirred students’ passions. Agee’s poignant prose, coupled with Evans’s compelling photos, puzzled and agonized them. They valued the exacting descriptions of the three Hale County families’ lives, but they found the overwrought prose tiresome at times. They loved Nate Shaw’s story of his long life. They admired his keen intellect and indomitable spirit. This story shows how working-class people maintain the dignity and resolve to surmount daunting obstacles, embrace community, and practice solidarity.

Primary texts form the cornerstone of course readings. Beginning with first-hand accounts recovers silenced voices, inspires archival and field research, and encourages students to curate and share what they find with broader audiences. We toured Auburn’s Special Collections and Archives. Undergrads wrote articles for the Encyclopedia of Alabama, an online compendium housed at Auburn. We developed a list of topics explored in Hammer and Hoe but not addressed in EoA, including the Alabama Communist Party, Southern Regional Council, labor leaders Hosea Hudson and Angelo Herndon, Southern Labor Review, The Southern Worker, and the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. Students were pleased with these possibilities, but the EoA staff ultimately rejected their manuscripts. Despite this, I will likely use this assignment again, because it gave students practice in professional/paid public writing and addressing a “real-world” rhetorical situation.

Graduate students performed primary research on working-class communities, and I required them to submit their completed work to a professional publication, providing an opportunity to practice key academic skills like reading submission guidelines and writing cover letters. Their projects included a comparative study of Hale County Schools’ technology education in the 1930s and 2010s; an account of working-class community groups struggling to wrest economic control of Phenix City, Alabama from corrupt elites; an examination of how whiteness is displaced as an “unmarked norm” in contemporary working-class literature; and a short story about class consciousness in Knoxville, Tennessee. In each case, students integrated primary and secondary research with original arguments to give voice to working-class subjects.

When we study the past, our ultimate goal is to gain insight into our zeitgeist. As labor journalist Stetson Kennedy points out, “The past, needless to say, has its place; namely, that of drawing conclusions for use in the present and future.” I supplemented our historical study with definitions of “the working class” and with contemporary arguments by writers such as Mike Rose (The Mind at Work), Barbara Ehrenreich (Nickel and Dimed), and Linda Tirado (Hand to Mouth). These and other readings help to engage students’ critical thinking about income and wealth inequality, poor health outcomes, poor job readiness, wage stagnation, and immigration. Instead of despairing, we focus on how to address working-class struggles. While student evaluations suggest that the reading load was heavy and dense, they valued the ideas and projects, which helped them think broadly and deeply about history, cultural identity, and political economy.

I decided upon a provocative topic in order to shock students to think critically about how history, culture, and experiences that seem natural are shaped by ideology. As Sven Beckert insists in Empire of Cotton: A Global History, cotton farming and trading brought on “war capitalism,” which shifted economic power from Asia to Europe on the backs of enslaved people. For centuries, King Cotton helped keep the Global Souths under the thumb of landowning gentry, Northern business interests, and now, international banking cabals and trade organizations—not an easy truth to accept. By focusing the course on the cotton industry, its workers, and its power, I want to provoke students to analyze propaganda, connect the dots of power structures, understand their heritage, perceive origins and manifestations of prejudices, and ultimately, act through speaking and writing to challenge hegemony.

Teaching these courses has also helped me connect my work with my history. On the first day of class, I tell students that my granddaddy was a sharecropper. And I use these five guiding principles to help them understand where they came from and how that knowledge might shape where they choose to go. At the end of the semester, I gave each graduate student a brick from the J.P. Stephens factory ruins in Opelika, Alabama—where Norma Rae was filmed. I keep in touch with several students who have told me they display the brick as a reminder of the course and how it changed their thinking.

Read the entire post and other Working-Class Perspectives posts on our website.

The Working-Class Perspectives blog is brought to you by our Visiting Scholar for the 2015-18 academic years, John Russo, and English Professor and Director of the American Studies Program at Georgetown University, Sherry Linkon. It features several regular and guest contributors. Last year, the blog published 43 posts that were read over 131,000 times by readers in 178 countries. The blog is cited by journalists from around the world, and discussed in courses in high schools and colleges worldwide.