WCP: Cultural and Political Diversity in the White Working-Class

Posted in News | Tagged Jack Metzgar, Working-Class Perspectives

All too often, political commentators describe working-class whites as if they were all the same — ignorant, backward, deplorable. But as Jack Metzgar writes in Working-Class Perspectives this week, not only is the working class larger and more diverse than public discourse often acknowledges, even the white part of the working class includes people with varied experiences and views, including many who are socially conservative but economically progressive. Even more important, Metzgar argues, if Biden can enact the economic policies he ran on, he could win support from considerable part of the white working class who voted for Trump but who are also open to a transformation toward economic justice that includes them.

Influential political analyst Ron Brownstein thinks American politics is all about answering this question: “How long can Paducah tell Seattle what to do?”

The question resonates because metro areas vote so differently from small town and rural areas and because our electoral-college leftover from slavery (like the Senate) gives these non-metro places outsized influence in our politics. Regionally, large majorities on the coasts vote Democratic while the South and Midwest are majority Republican. But to Brownstein’s readers in The Atlantic, Paducah (population 23,000 and in Kentucky) likely also connotes “hick” or “hillbilly,” terms that are stand-ins for “poorly educated” whites without bachelor’s degrees — or the so-called white working class.

Brownstein presents the core conflict in American politics as between a backward-looking, aggrieved “coalition of restoration” (Paducah) and a forward-looking, virtuous “coalition of transformation” (Seattle). The unstated assumption is that highly educated folks, the transformers, are the norm as well as the ideal, whereas poorly educated whites are ignorant and backward at best, or deplorable at worst. Those whites seemed to prove that again last Tuesday by voting 64 to 35 for Donald J. Trump. (All 2020 election results here are from preliminary and not entirely reliable Edison exit polls as reported in The New York Times.)

At this moment it’s pretty tempting for us highly educated folks to think that all Trump voters are deplorable people resisting the important transformations we are all busy working toward. But there are different transformations afoot and they’re not all positive. And there’s also some restoration we could use a lot more of.

Brownstein mistakenly meshes cultural transformations – “growing diversity in race, religion, and sexual orientation [and] evolving roles for women” – with economic ones – “the move from an industrial economy to one grounded in the Information Age.” In this formulation if you want to restore some important aspects of the Industrial Age – like 2% annual increases in real wages for three decades, strong unions, and steeply progressive taxes – then you also resist growing diversity and evolving roles for women.

It’s true that many white men, with and without bachelor’s degrees, rage against all three transformations. But there is no logical connection between cultural reactionaries and economic ones. A person can be culturally deplorable and economically progressive at the same time, as much survey research has shown. Or they can resist diversity but be open to – and in fact, looking for – the government to dramatically improve their economic circumstances. And that means that Democrats should make a renewed effort to convince workers of all skin tones to look more closely at their economic program. The one Biden ran on is good enough.

It didn’t get much attention in the media, nor did Biden emphasize it enough. Yet the economic program Biden ran on is potentially transformative at the scale he proposed – especially trade and industrial policies focused on making more things in-country, a massive infrastructure investment that creates millions of jobs, and a comprehensive enhancement of the care economy for children, elders, and the workers who care for them, all paid for with increased taxes on corporations and the wealthy. If enacted, this program will disproportionately benefit people of color, but the largest group of beneficiaries will be whites without bachelor’s degrees.

Such a program will be impossible to enact with a Senate still controlled by Paducah, but the overall program could be enormously popular, and it should be the center of Democratic legislative politics for the next two years. The program – and the focus on economic revival – might be able to pull a handful of Republican senators across the aisle, but that’s not as important as making strong inroads into the Trumpian base of the party – namely, the white working class. I believe that can be done and is, in fact, highly feasible, but you have to understand the Trump coalition better than our punditry generally does.

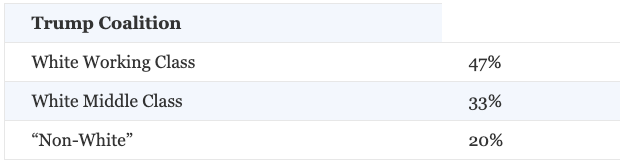

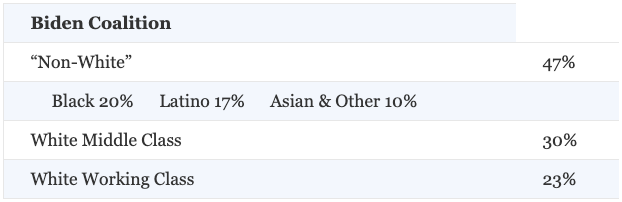

A recent New York Times article, for example, described the Trump and Biden coalitions in a way that is quite common shorthand among many analysts and pundits: “A Trump coalition of white voters without college degrees and a Biden coalition of college-educated white voters . . . and minority voters.”

White people without bachelor’s degrees are the largest part of the Trump coalition – 47% — but they are not alone. Despite what Brownstein and others assume, the white part of the educated middle class are not uniformly right-thinking transformers. Last week they split their vote 49 to 49, making them about a third of the Trump coalition.

While only a fifth of the Trump coalition are not white, “non-white” people make up nearly half of Biden’s coalition. The total “non-white” Dem advantage may be down some from the Obama elections, but it is still huge. As growing and mobilizing parts of the electorate, racial minorities are clearly the foundation of any viable Democratic coalition.

But that 35% minority of working-class whites who voted for Biden are not an insubstantial part of the Biden coalition, making up nearly a quarter of it. That’s the smallest part of the coalition, but it amounts to about 20 million voters, which is more people than reside in all but four of our most populous states. The educated white middle class represents a somewhat larger group, but they are not the only white part of the Democratic coalition.

Simple democratic arithmetic dictates that you cannot neglect any part of your coalition, but you also need to add to your coalition by subtracting from the opposition’s groups. The white working class may have gotten over-sized attention from progressive Democrats coming into this election, but that’s because they are the single biggest target. It didn’t help that a part of the Democratic party has sometimes argued that they should be abandoned and allowed to stew in their own juices – often with more than a little class prejudice. Democrats’ effort to attract more working-class whites, however, resulted in about a 4-point gain among them nationally, but the gains in battleground Rust Belt states were enough to determine outcomes – 8 points in Michigan, 9 points in Minnesota, 7 points in Wisconsin, though only 2 points in Pennsylvania.

As Michael Sandel has pointed out, “Disdain for the Less Educated Is the Last Acceptable Prejudice.” To gain more support from working-class whites, Democrats have to acknowledge that class prejudice — and overcome it. We can start by simply understanding that the white working class is a very large and diverse group of people. It cannot reasonably be characterized as having one uniform social and political psychology. Indeed, it is so large and diverse that it makes up both the largest piece of the Trump base and an indispensable part of the Biden base.

Nor should we buy the kind of broad-brush geographical references that Brownstein offers. Working-class whites don’t all live in places like Paducah. They live in cities, including Seattle, and are likely a majority in the suburbs, even though political reporters often seem to assume that “the suburbs” require a bachelor’s degree and a comfortable income for admission.

Most important, we need to understand that while some part of the white working class is deplorable in every respect, the largest group among them is culturally conservative but also economically progressive. The Public Religion Research Institute study that tracked substantial racial and cultural resentments and anxieties among large portions of the white working class also found:

White working-class Americans generally believe the economic system is stacked against them, are broadly supportive of populist economic policies such as raising the minimum wage and taxing the wealthy—including a larger role for government—and are skeptical of free trade. . . . . Most white working-class Americans believe the best way to promote economic growth is to increase spending on education and the nation’s infrastructure, while raising taxes on wealthy individuals and businesses to pay for it.”

If a President Joe-from-Scranton can unify Democratic legislators around the progressive economic program he ran on, he can rally the diverse coalition that elected him this year while at the same time appealing to that considerable part of the white working class who voted for Trump but who are also open to a transformation toward economic justice that includes them.

Jack Metzgar

Jack Metzgar is a professor emeritus of Humanities at Roosevelt University in Chicago. A former president of the Working-Class Studies Association, he is the author of a forthcoming book from Cornell University Press, No One Right Way: Working-Class Culture in a Middle-Class Society.

Read other Working-Class Perspectives on our website.

The Working-Class Perspectives blog is brought to you by our Visiting Scholar for the 2015-20 academic years, John Russo, and English Professor and Director of the American Studies Program at Georgetown University, Sherry Linkon. It features several regular and guest contributors. Last year, the blog published 43 posts that were read over 94,000 times by readers in 176 countries. The blog is cited by journalists from around the world, and discussed in courses in high schools and colleges worldwide.